Monday, August 15, 2022, marks the 75th anniversary of the Partition of Panjab.

I could finally visit my father in Delhi in March of this year. It was a much-needed visit after a three-year separation due to Covid restrictions. My goal was to spend most of my five weeks with him – which I did. There is something to be said about just being present. One does not need to fill every moment with chatter. Sometimes just being there is enough for the most profound conversations to flow.

One evening while watching the news, Dad turned to me and said, “Will they (Ukrainians) ever return? We never did?” At that moment, I realized the depth of his pain; though he rarely speaks about it, Partition is still with him. The sadness in his words spoke volumes. The memories of his ancestral homes in Chakwal and Jhelum were still with him.

Seventy-five years have passed since the Partition of Panjab and the creation of India and Pakistan. And yet, the longing to go back has not waned. At one level, my practical father says, “It’s all gone. There is no point in remembering?” And yet, he remembers and sort of grieves.

On one of my earlier visits, I insisted he tell me what happened to the family during Partition. He tested my powers of persuasion. But finally, he relented, and we began the recorded sessions.

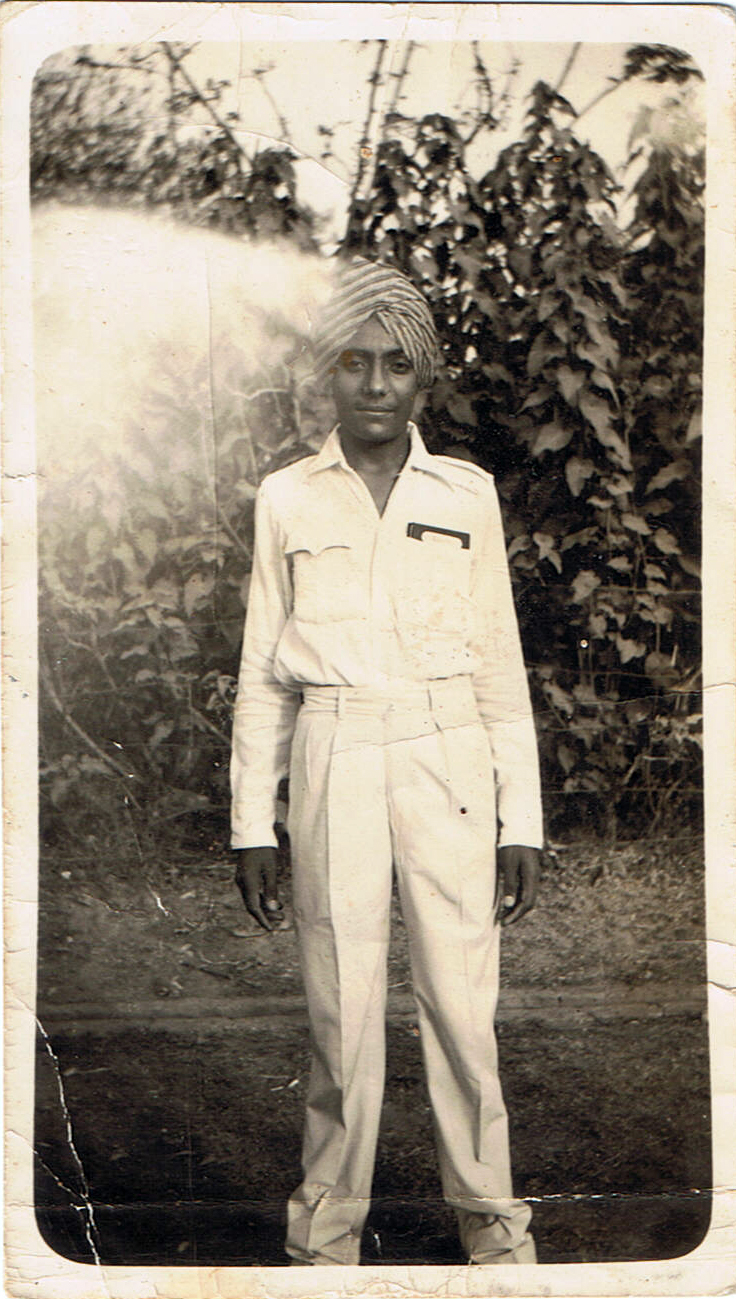

The following is the story of my father, Bawa Gurnam Singh (b. 1931 – Chakwal, Dist. Jhelum, pre-partition Panjab), son of Harnam Kaur and Hari Singh Bawa. As relayed to me by my father:

* * * * *

“You know, during Partition, I got saved twice in one day. I was 16 years old and was staying with my Nana ji (maternal grandfather) Mehtab Singh Maini in Jhelum. He was a Congress leader who was constantly in and out of jail.

“While those times were challenging, they were also interesting. Every influential leader used to stay at Nana ji’s big home. The main house was for the family, and the exterior was for guests.

“At that time, in Jhelum, daily protests against the British Government used to be daily. The women led their processions - Nani ji (maternal grandmother) also marched. The youngsters were the most vocal. I was actively involved in politics. Therefore, subject to several police beatings. It was their way of getting back at Nana ji.”

“Dad, how old were you during these beatings?”

“I was in grades 7 and 8 studying at the Khalsa School in Jhelum when the beatings occurred. The police used to come to our school, pick up a few other boys and me, take us to the police station, thrash us and send us back home. I remember one particular beating. The police officers were beating us lightly. I guess they felt sorry for us because we were children. A British Officer saw what was happening. He immediately came over, took the cane from the police officer, and thrashed us. I still remember that beating. But that was life in those days.

“In August 1947, I was in the 10th grade and back in Jhelum for the school holidays. Nana ji’s home was the political hub. Everyone came there to get and give information. One day, Inder Singh Gadhok and his younger brother Dilbagh Singh came to inform Nana ji that they were leaving for Ambala. The Muslim community had hired them to bring back their Pir (saint) living there. The two brothers and Sri Ram, the driver, were leaving the next day by bus.

“I knew Inder Singh very well. He was the don of Chakwal. Nobody dared to cross him. He greatly loved and respected my taya ji (father’s older brother - Bawa Jewan Singh). Inder had ensured everyone knew that our family was under his protection.”

“Dad, a don?”

“Yup! Something like today’s mafia. Inder controlled a large part of the bus transportation in Panjab. I used to ride for free on the buses because of him.”

I’m flabbergasted. I make a mental note: I have to learn more about Inder. But not right now.

“I was eager to see the Independence Day celebrations in Delhi. My older brother Amrik Singh was studying at the Delhi Polytechnic College and staying at the Kashmiri Gate hostel. I begged and pleaded with Nana ji to allow me to go with Inder to Amritsar. From there, I would catch the train to Delhi. With great reluctance, Nana ji agreed.

“The following day, I left. Inder drove the bus up to Lahore. When we entered Lahore, he told Sri Ram to take over as we entered the Muslim area. So, Sri Ram drove, and the three of us lay down on the seats hidden from public view. But Sri Ram did not know the way and constantly asked Inder for directions. He came to a critical junction and did not know where to turn. Inder got up to see where we were. At that moment, the people on the ground saw that there was a Sardar on the bus. They started shouting, and before you knew it, they threw a small bomb at our bus. It hit the rear wheel tire of the bus. The tire exploded, causing a huge sound.

“A predominantly Muslim crowd immediately surrounded the bus. Just then, an army unit passed by and stopped to see what was happening. The group told them we were terrorists and were throwing bombs at them.

“Inder, of course, protested. The army officer decided to search our bus. When he opened Inder’s suitcase, a photograph caught his eye. He asked Inder how he got this photograph. Inder told him that it was his childhood photograph. The officer looked shocked. It turned out that he was Inder’s childhood friend, Hussain, who had left Chakwal many years ago. Hussain was thrilled to reconnect with Inder.

“Under Hussain’s protection, the repair of the bus tire happened, and we were escorted to Mughalpura, a part of town that was Sikh and Hindu-dominated. Hussain said we would be safe here and should leave for Amritsar from Mughalpura.

“We spent that night at Inder’s relative’s home in Mughalpura. In the middle of the night, Inder woke us up. He said that he had an eerie feeling and that we should leave immediately. He was sure something terrible was going to happen. He insisted that his relatives leave with him, but they refused, assuring him they were safe.

“The four of us got on the bus and left for Amritsar immediately. When we reached Amritsar, we heard that the Muslims attacked Mughalpura and killed everyone. We had narrowly escaped death.

“Inder dropped me off at the Amritsar railway station and proceeded to Ambala. At the station, I could not get a ticket for Delhi. The Government had stopped all trains going into Delhi. I guess they did not want refugees coming into the capital and disrupting the celebrations. I sat at the train station for four days, during which my luggage and money got stolen. My passport and a few photographs in a muslin bag hanging from my neck under my shirt were all I had left. Nana ji had insisted that I carry my passport that way. I had a British Indian passport, stamped in red: ‘Son of a revolutionary.’”

“Wow! ‘Son of a revolutionary?’ How did you feel about that, Dad?”

“Great! It was like a badge of honor. The people who used to help the British Government got titles like ‘Sardar Bahadar,’ ‘Sardar Sahib,’ ‘Khan Bahadur,’ and ‘Khan Sahib,’ and many such phokat (hollow) titles. Local equivalents of ‘Sir’ and knighthoods, they were. There used to be weekly processions in front of these people’s homes. They were gadhars (traitors). We were real heroes fighting for our freedom.”

“Dad, what did you do for food? You had no money?”

“Food was no problem. There was free food available at the station for the refugees. On the fourth day, a long train with a large sign saying ‘Delhi’ arrived at the station. Everyone, including me, boarded that train, thinking we were going to Delhi. But, that was not the case. The train was heading for Patiala.

“I knew my mother’s sister Rani and husband Amar Singh Ghai lived in Patiala, but I did not have their address. Talk about being lucky! As I left the train station, a tongawala (a horse-carriage driver) stopped me. I recognized him immediately. He was Kala from Chakwal. I told him all that had happened since I had left Jhelum. He insisted I stay with him and ride with him until I found my relatives. I hesitated at first. But I had no choice, so I agreed.”

“Dad, why did you hesitate?”

“He was a dangotara.”

“Who, what, is a dangotara?”

“Dangotras in Chakwal were beggars. A few of them did odd jobs. Every Saturday, they would go begging door to door. They used to carry a small bowl, which had mustard oil and a small idol in it. People would put money in their bowls. But Kala did not beg. He owned his tonga (horse carriage). In 1942, when we came from Zaidan, Iran, to get my eldest sister Jasbir bhen ji married, my father hired Kala for the entire wedding month. Kala was in charge of getting everyone from the train station and delivering all the supplies from the market to our home. So, I knew him well.

“Kala took me to his home, a small two-room house. His wife and children were also there. I remember he gave me his best charpai (cot) to sleep on.

“On the third day of riding around Patiala, I spotted my uncle carrying a bag of vegetables. I immediately asked Kala to stop and ran to my uncle. My uncle was shocked to see me and took me home. I stayed with my aunt and uncle for five days. They were very, very nice to me. They got clothes for me, gave me money and bought my train ticket to Delhi.

“When I arrived in Delhi, I went straight to my brother Amrik’s hostel in Kashmiri Gate and knocked on Room 302. Amrik opened the door and was stunned to see me. Are you alive? Are you really alive? He kept asking. I was surprised by his question.

“He then told me that Nana ji had read in the Urdu paper Milap that the bus I was on was attacked in Lahore, and no one had survived. The family thinks you are dead. He rushed to the post office and sent two telegrams: one to our parents in Zaidan and the other to Nana ji in Jhelum, informing them all that I was alive. Years later, I discovered that my parents had said my antim ardas (final prayers) in Zaidan.

“For two months, I stayed with Amrik at his hostel. It was against hostel rules. But there was nowhere else I could stay.”

“Dad, what was Delhi like in August of 1947? What did you do for those two months?”

“I don’t know what was happening in all of Delhi. I can only say what was happening in my area. It seemed calm. I did not see any organized mobs. Though, I did see a few stabbings. Amrik’s friend Sayali advised me to join the NCC (National Cadet Corp.). So I registered at the Kashmiri Gate Police Station within walking distance of the hostel.

“Every morning at 8 a.m., I would go to the police station. Two policemen and I would then go in a jeep to rescue Muslims. We used to go door to door, as the houses in Kashmiri Gate were in small lanes. I remember one time entering a place that looked empty. But it was not. There was a young girl around 14 - 15 years old hiding there. When she saw me, she started screaming. I calmed her down with great difficulty and told her I was there to help, not harm her. Her entire family had left without her. We took her back to the police station, and she was taken by bus to the Purana Qila (Old Fort) Refugee Camp.

“I spent two months in Delhi this way. I used to have lunch at the police station and sneak back into the hostel at night. I got caught the day Amrik went to Rohtak. The warden insisted that I leave the hostel immediately. Amrik’s friends did not take to this very kindly. They held their ground and said that I was not to go. To keep the peace, the warden took me to his home. I stayed with him for three days until Amrik got back. The warden’s home was far nicer than the hostel.

“Amrik had gone to Rohtak to see if our Mama ji (mother’s brother), Dr. Darshan Singh Maini, and his wife, Tejinder, were willing to have me stay with them and complete my studies. They, of course, agreed. Darshan mama ji had just gotten a job at the Government College. That was the good news.

“Then Amrik told me that Nana ji was dead. My whole world came to a standstill. I adored my Nana ji. He was the biggest influence in my life. He really loved me. I learned so much from him. Because of him, I joined the Congress Party, even though my father was an Akali.”

ROHTAK

“In Rohtak, I joined the Government High School. But the school was closed. There was nothing to do. So I volunteered at the Rohtak Refugee Camp.

“The camp was an open field near the High School. Admiral Gurdeep Singh, a retired navy officer, was in charge of the camp. He ran a very tight ship. We were about twenty volunteers, and I was responsible for the rations. I worked at that camp for five to six months.”

“But Dad, you were so young? How come you had such an important charge?”

“I worked very hard. I spent all my waking hours at camp. I would only go home to wash up and change. The rest of the time, I was at camp.

“I remember when Sarojini Naidu, a well-known poet, and freedom fighter, visited our camp. Admiral Gurdeep Singh introduced me to her as head of rations. She was also very surprised to see a sixteen-year-old in such an important position.”

“What was the camp like? What were you doing there?”

“I was managing the rations and doing whatever was required. There were nineteen items on ration at our camp – spices, medicines, quilts, rice, lentils, etc. The rations came from Delhi and were stored at the high school. Gurdeep Singh would send a telegram listing what was needed. The next day the trucks delivered them. We had about 20-30 trucks delivering supplies every day.

“As far as I remember, there were no Sikh refugees at our camp. Most of the refugees were from Multan. The men were big and hardworking. They were the ones who unloaded the trucks and stored the rations. Each man would carry a sack of 100 kilos of rice on his back. They were the ones who put up the tents and the toilets and did all the manual work at camp. No labor was hired to do any of the work.

“Running the camp was not difficult because the refugees helped a lot. The biggest problem was the fights they had amongst themselves. Almost every day, part of our jobs was to settle their disputes.

“The only thing that was difficult at camp was providing security for the young orphaned girls. Gurdeep Singh had a special section right in the middle of the camp next to his office for them. He had barbed wire going around those tents and guards protecting the girls. I think there were about thirty girls. He sort of adopted them. He got them trained, married, and gave each one a sewing machine and Rs. 500 from his personal finances.”

“So, Dad, there seemed to be a government in place?”

“Of course, there was. There never was a fight at camp over rations. But the mood was very sad. Everyone was crying. They had lost all their belongings; some had lost family. I used to cry a lot listening to their stories. Mami ji (aunt) used to get angry seeing my swollen eyes and dirt-filled clothes. She wanted me to stop volunteering, but I didn’t.

“Living conditions were hard at camp. At one point, we had about 400,000 refugees. Slowly people began to move out. When the orders came to close the camp, we were down to about 50,000 refugees. They were asked to leave, which was not easy.

“I must say, Gurdeep Singh did a remarkable job. He was an amazing man. I salute him.

“The school eventually reopened, and I joined the High School. I had a good friend in Ishar Singh, who had volunteered at camp. I think that friendship helped greatly in settling down in Rohtak.”

“Dad, what are your thoughts about the Partition?”

“Partition was like separating your children. It was so wrong. I don’t think anyone could have imagined what happened. Nana ji, who was a Congress leader, never for a moment thought that he would have to leave Jhelum. Partition changed everything. Our home, our land in Chakwal, everything was gone. All my childhood connections were lost. I never went back.”

Dad goes silent.

My mind drifts …

I want to know more about my great grandfather, Bhai Mehtab Singh Maini (1880 - 1947, son of Bhagwan Singh and Sarasti Devi – Pind Vahalee, District Jhelum).

I reach out to his son.

“Uncle ji, tell me what happened to you during the Partition?”

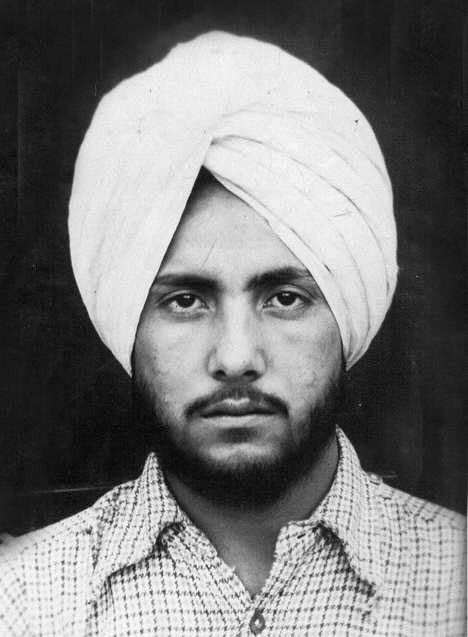

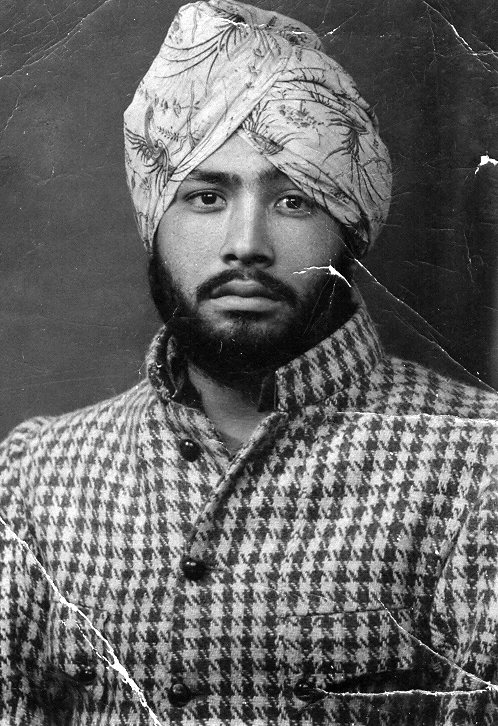

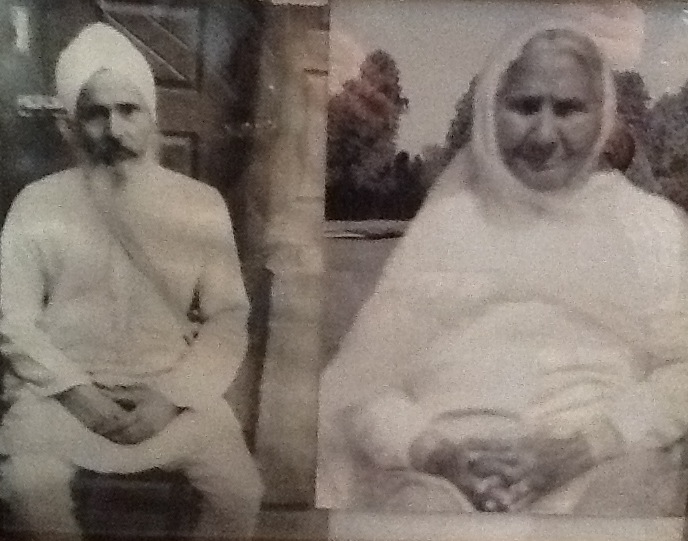

The following narration is by Sarmukh Singh Maini (1928-2019), son of Mehtab Singh and Budhwanti Kaur.

.jpeg)

* * * * *

“Dear Inni, in all these years, you are the only one who has asked, (he says).

“I was in my final year of high school (matric) during the time of Partition. We were eight siblings. In August of 1947, my sister Tej Kaur, my brother Trilochan Singh, and I were the only ones left with our parents in Jhelum. By mid-August, Dar ji (father) sent my brother and sister to Amritsar with our very good friend Sardar Avtar Singh. His son had come with a military truck to evacuate his family. So I was the only child that was with our parents.

“I can still hear Dar ji’s voice: ‘So what if there is a Pakistan? It does not mean we have to leave Jhelum.’

“But things in Jhelum began deteriorating rapidly after August 15. Our home was in Machine Mohalla No. 1. (Machine Mohalla 2 was a Hindu area; Machine Mohalla 3 was a Muslim area). Our family had three interconnected houses. My two uncles (Dar ji’s brothers: Sant Singh and Sardar Singh) had their homes on either side. We could reach each other’s homes via the roof.

“One September morning, many Hindu and Sikh families came to our home to seek refuge. The Muslim mob forced them out and took over their homes. By that afternoon, there were about 3000 people in our homes.

“Around 5 pm that day, the Muslim mob stood outside our home and began shooting. Many people knew that Dar ji did not own a gun. But we had one gun in the house that belonged to my cousin. Dar ji grabbed that gun and started firing back at the mob. The shooting went on for about an hour or two. I was handing Dar ji kartoos (cartridges) I had put in my pockets.

“At 7.30 p.m., the mob began to torch the house. The fire started raging from all sides. We had to evacuate and come out in the open. We walked towards the police station through the small bazaar behind our home. I was walking with my parents on either side. None of us saw the gunman sitting on the roof of one of the Sikh homes.

“He fired on Dar ji. I am sure Dar ji was his target. The bullet hit Dar ji’s left thigh. I immediately had Dar ji lean on me. We struggled and walked another 100 yards to the police station. The police station was barely 200 yards from the house.

“The police could hear the firing, but they did not come to help. While walking toward the police station, I saw a constable and requested his help in reaching the police station. Instead of helping us, he spat on us, saying that we were kafirs (infidels). Dar ji knew this constable. The police station was overcrowded. It seemed like every Hindu and Sikh family from our area was there.

“I remember Dar ji asking me for water at the police station. He was bleeding heavily. I could not leave him. I asked the constables if they could bring me some water. None did. Dar ji knew all of these constables.

“Suddenly, I saw Narpat Rai Khairati, a very good friend of Dar ji’s. He lived about 500 yards from our home. He immediately went to the hand pump, wet his white turban, and poured water into Dar ji’s mouth.

“All the wounded people were put in a truck and taken to the Civilian hospital.

“Although I was not hurt, my clothes were drenched with Dar ji’s blood. I, too, boarded the truck. Dar ji was in a semi-conscious state. By now, it had gotten dark. I emptied my pockets of the remaining bullets and threw them from the truck. Then I removed Dar ji’s gatra (belt), which held his kirpan, his gold pocket watch, and Rs. 5000, and put them in my pockets.

“I was hoping that he would get the proper treatment and survive. But soon after we arrived at the hospital, he died in my arms. A few of my friends also died that day.

“The following morning, I, along with the others, was taken by the police to the main Gurduara, declared a refugee camp. The police took away Dar ji’s kirpan from me.

“When I got to the Gurduara, I told Bey ji (mother) that Dar ji was no more. She went silent. From that moment on, she focused her full attention on me. I was in a state of shock. She kept saying: it will be alright, it will be alright.

“Bey ji and I stayed at Ramey Shah’s home opposite the Gurduara Singh Sabha for a few days. Ramey Shah was a kind and good man. He knew us very well. His house was on the banks of the river Jhelum. That area was safe at that time.

“After five days, twelve trucks came to the Gurduara to begin evacuating 10,000 people. There was such a rush to get onto the trucks. Bey ji couldn't jump up on the truck, so we returned to Ramey Shah’s home.

“The following day, around 10 a.m., I heard my name being broadcast via a loudspeaker on the road. There was a message for me to appear with Bey ji by order of the Indian Government representative Lala Avtar Narain (father of ex-PM Inder Gujral).

“Ramey Shah requested us to take his young daughter as well. He stayed behind. So, the three of us sat in the car that had an armed escort. The car took us to the truck convoy in the Cantonment area. The convoy was waiting for us. We boarded the truck and headed to India.

“At the town of Gujranwala, our convoy was held up for 8-10 days due to floods. We slept on the ground. There was hardly any food. We were lucky if we got one roti a day. It was terrible. This is how we reached Amritsar.

“My elder brother was waiting for us. He did not know that our father had been killed. You should have heard him weep when he heard the news.”

Uncle goes silent. It’s a similar silence that I experienced when my father narrated his story.

Gently, I ask, “Uncle ji, did you go back to see if your house survived?”

“No. It was not safe to go to that area. But I now know that our home has been converted into a mosque. Can you believe that?”

I pause to digest this. A mosque!

“Uncle ji, do you remember the date when this happened?”

“I think it was September 25, 1947. But I am not too sure. I was in such a state of shock. Everything was gone. I knew nothing would ever be the same again.

“Please tell me a little more about Dar ji’s life.”

“Bey ji was from a Hindu family. She was one of seven sisters. Her father wanted one Sikh son-in-law. So, he got her married to Dar ji. Bey ji was illiterate when she got married. Dar ji taught her Gurmukhi, and she became a staunch Sikh under his influence. That tells you how important his Sikhi was to him.

“He was a great hunter and a horseman. One year at the mela in Jhelum, he accepted a challenge to ride a beautiful wild horse. The owner of the horse was confident of winning. Well! Dar ji jumped on the horse and rode it like a champ. He was in his early forties then.

“In 1930, he was jailed in Gujarat for over a year under the Civil Disobedience Movement. It was a terrible time. The business suffered greatly.

“He was a member of Chief Khalsa Diwan and used to go to Amritsar every two months for their meetings. He was in Amritsar in July of 1947 for a meeting. He was also the President of the Gurduara Choa Sahib (Rohtas, Jhelum).

“Sant Suraj Singh, the Panjabi poet, used to stay with us regularly. He had written a book Jagrit Khalsa in verse against the British Raj. Dar ji got the book published. When the book hit the market, the police immediately came to our home and confiscated the entire print run.

“I remember one Vaisakhi: Baba Kharak Singh came to deliver a lecture at the Choa Sahib Gurduara. British intelligence found out. They and the local constables arrived at the Gurduara to arrest him. The Sikhs immediately formed a circle around Baba ji. The British Officer told Dar ji that he would have to use force if prevented from arresting Baba ji. Dar ji told them they could arrest Baba ji after the lecture but not before. They reached an agreement. Baba Kharak Singh was arrested after he delivered the lecture at the Gurduara without the use of force.”

Scenes from the film “The Last Samurai” flash before me.

I can see Dar ji in action.

I know how he died, but the hunger to know how he lived gnaws me.

Article first appeared on 12 August 2013 on Sikhchic.com

.svg)

.svg)

.png)

.svg)